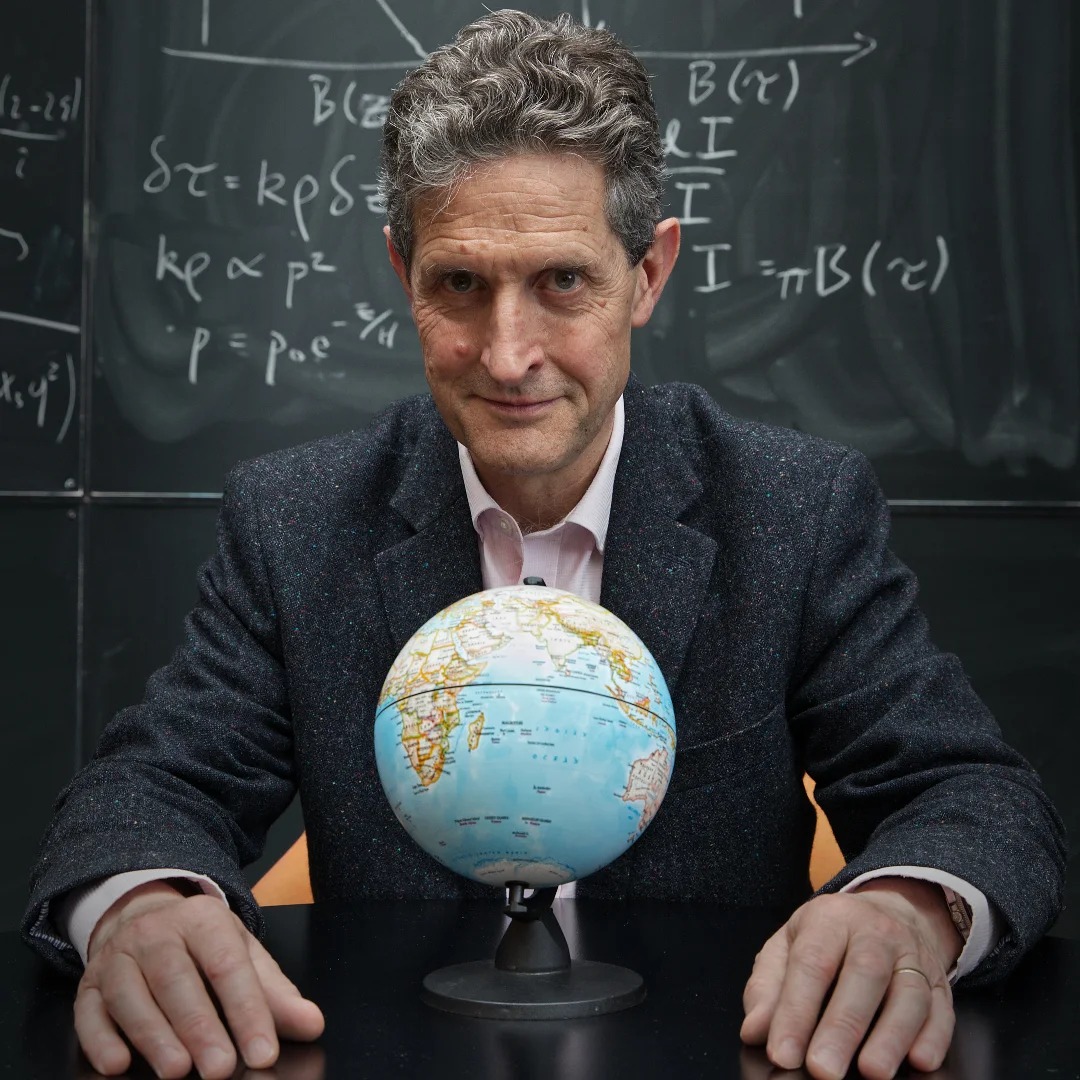

This week, world-renowned climate physicist Professor Myles Allen delivered a thought-provoking lecture at Gresham College titled “Does Net Zero Mean the End of Livestock Agriculture?” His answer: no — provided we get the science, and the metrics, right.

Instead, he argued that this narrative is based on outdated climate metrics and a misunderstanding of how different greenhouse gases behave.

Allen’s work is based on the fact that not all greenhouse gases are created equal. Unlike carbon dioxide (CO₂), which can remain in the atmosphere for centuries, methane breaks down in about a decade.

This matters because the commonly used GWP100 metric — which equates a tonne of methane to 28 tonnes of CO₂ over a 100-year period — fails to capture the crucial difference in lifespan between the two gases. As a result, the climate impact of livestock methane is routinely overstated in net zero accounting.

Professor Allen has developed a newer metric that better reflects methane’s real warming effect – and the fact that measuring grazed livestock’s impact is a two sided balance sheet of emissions minus carbon sequestration. Unlike GWP100, GWP* considers whether methane emissions are increasing or decreasing over time. A stable or declining rate of methane emissions leads to little or no additional warming — and could even be cooling.

This shift in perspective has big implications. It means that a sheep or cattle farm that is not expanding its herd — and perhaps even reducing it — may not be contributing to further global warming at all, despite still emitting methane.

Thanks to improvements in productivity which has led to a gradual reduction in herd sizes, UK methane emissions from agriculture have been falling for decades. As a result, British livestock farming is no longer adding to global warming.

This runs counter to many policy narratives, which continue to target livestock as a key emissions source. Allen warned that unless the science is reflected in policy, farmers may be unfairly penalised — or worse, pushed out of business — for emissions that are not driving climate change.

Professor Allen’s central plea was for policymakers to use the right tools for the job. If we are serious about tackling global warming, we need to measure what matters: the actual effect of emissions on the climate. That means moving away from simplistic carbon accounting and embracing more nuanced approaches like GWP*.

But he also reminded the audience that methane reduction has a unique potential because it breaks down so quickly. Targeted cuts can therefore offer relatively rapid climate benefits. But that doesn’t mean all methane emissions must go. Stable, well-managed livestock systems can co-exist with climate goals — and should be part of the solution, not scapegoated as the problem.

Professor Myles Allen’s lecture was a timely reminder that climate science is complex — and that getting it wrong can have real consequences for livelihoods and food systems. For the British meat and livestock industry, his insights offer both reassurance and a roadmap: keep emissions stable or falling, push for smarter metrics, and demand that climate policies are built on sound science.

We are the UKs largest trade body for the meat industry and provide expert advice on trade issues, bespoke technical advice and access to government policy makers

We are proud to count businesses of all sizes and specialties as members. They range from small, family run abattoirs serving local customers to the largest meat processing companies responsible for supplying some of our best-loved brands to shops and supermarkets.

We are further strengthened by our associate Members who work in industries that support and supply our meat processing companies.

We are the voice of the British meat industry.

17 Clerkenwell Green

Clerkenwell, EC1 0DP

Tel: 020 7329 0776