Some argue that a major dividend of leaving the EU is that we can develop ‘better’ regulation, presumably with an economic benefit of some sort, and that the EU’s regulatory regime is a brake on developing trade with export markets.

This is an illusion, and we need to understand the risks we run if we decide to go down this path. Even the sort of creeping divergence that occurs as EU rules change and ours don’t will make things more difficult.

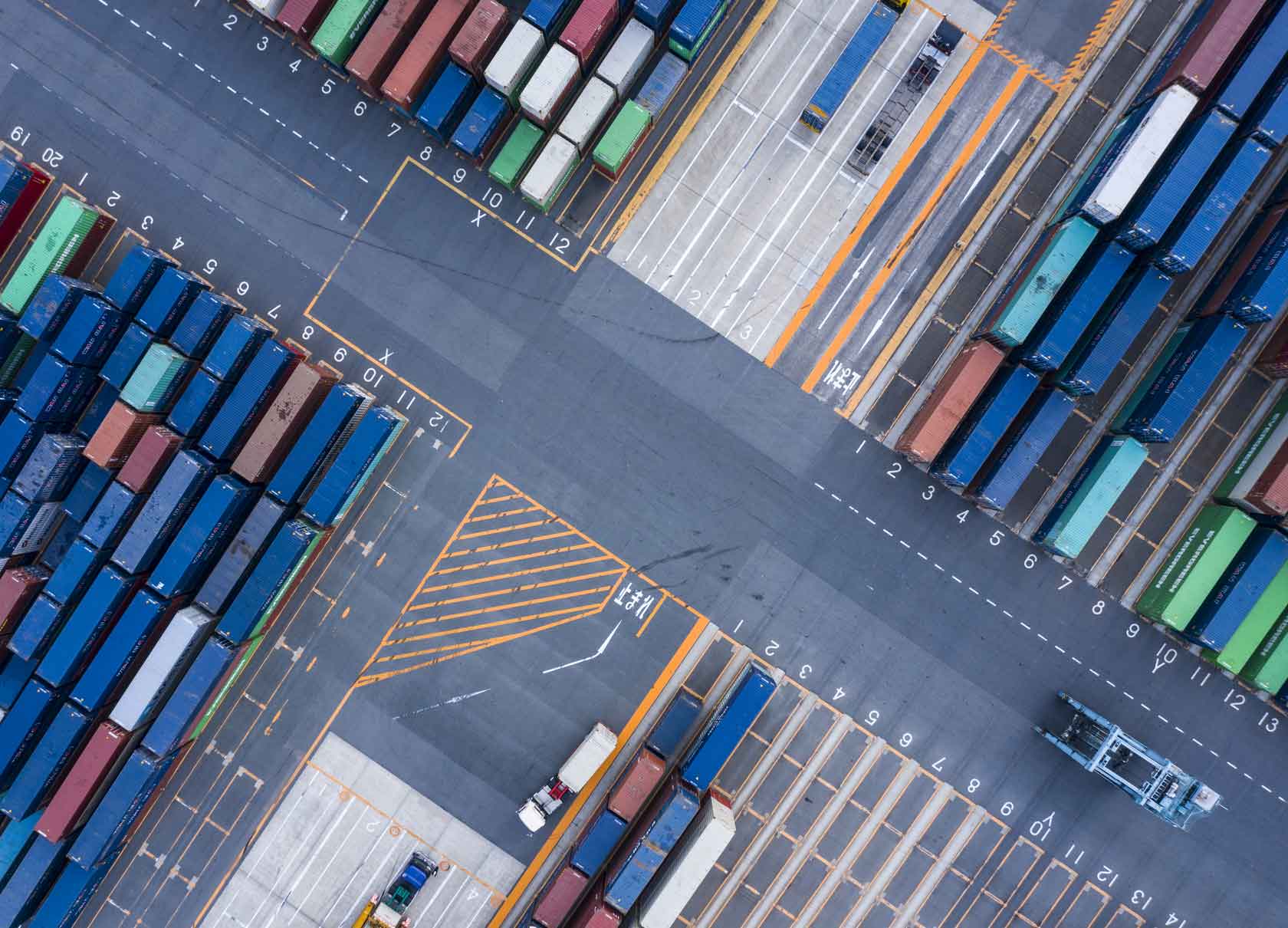

The EU is and will remain our largest and highest value market. For those who believe that we should just pursue opportunities elsewhere, let’s get real. Our exporters aren’t fools, and if they could make much more money exporting greater volumes further afield, they would. To put this in perspective, in 2023 the EU market for beef has been over twice as valuable per tonne as non-EU. While non-EU markets represent 17% of exports, they only account for 9% of export value. The corresponding ratios of value per tonne for sheepmeat and pork are 36% and 22% respectively, so the EU remains a priority market.

Let’s dispel the myth that somehow, we can do trade deals more easily if we are not aligned with EU rules. First, not one of the new FTA’s the UK has signed has been hampered by this despite the fact that we remain more or less aligned. None of those agreements contains anything but cursory references to SPS and are certainly not contingent on any form of equivalence agreement. In fact, where we have secured export certification for export markets, this has always been underpinned by EU standards, which has proved an advantage in terms of market access for our exporters. If the proponents are suggesting that we should drop our standards and allow the import of meat produced using practices that we do not allow, then this would be contrary to our commitments never to do so.

Second, the simple reality is that, to supply our largest market, our farms and meat plants must comply fully with all of the provisions of the EU’s public and animal health rules even if our rules change. It makes no difference if we choose to diverge, but if we do, we must deal with the massive complexity and extra cost of having multiple production streams in our supply chains. In short, given that we are already complying but still having to jump through all the certification and SPS control hoops to prove it with no added value, alignment would save hundreds of millions of pounds.

Finally, there is the downside risk of both deliberate and creeping divergence. Creeping divergence can be accommodated to a degree as farmers and processors adapt and comply with any new requirements as they emerge. But some aspects of divergence cannot be accommodated and threaten to undermine our ability to supply the EU market. An example of this is the new Border Target Operating Model which will simplify the certification requirements of exporters to the UK and reduce the level and frequency of import controls based on risk categorisation. As this differs from the EU approach it means that the EU may need to re-evaluate the biosecurity risk posed by product coming from UK, which may result in the need to provide additional guarantees or worse.

The time is ripe, before it is too late, to stop the clock on further divergence, save farmers and processors a fortune in costs for something that they are already doing, and reach an alignment agreement with the EU.

About BMPA

The British Meat Processors Association (BMPA) is the leading trade association for the meat and meat products industry in the UK. Our members collectively employ over 75,000 people in the UK and the industry is worth over £12 billion a year to the British Economy.

For more information about this topic or to speak to an expert contact us.